Quite happy with my recent purchase of a small booklet of prints from the weekend flea market. I was only interested in the first 7 or so photographs but there was no way to purchase them without tearing the booklet. The negatives were unfortunately nowhere to be found. One booth had a small box of empty envelopes used to store negatives but in all likelihood the negatives would have been discarded as it has very little value to anyone unfamiliar with making prints. The envelopes that housed them on the other hand had names, dates, and addresses printed/written on them, a clear marker of its value as an antique.

This booklet of prints were produced by Shui Kat & Co., almost certainly by the lab in 113, High St. (today Jalan Tun H S Lee), K. Lumpur as the roll included photographs around Brickfields.

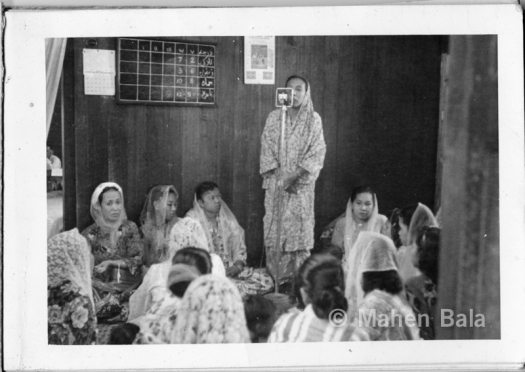

Appended below are scans of the first 7 prints, which look as if they were exposed at the same event. Photographs of the kenduri was particularly interesting as it depicts a normal, unstaged scene where locals are eating, drinking, going about their day like any other. Here we have a chance to observe a distinctly Malayan way of life, and consider how much, if at all, things have changed since then.

The tradition of the kenduri is still very much alive, accompanying every important function with its own distinct food, performances and decorations according to the local preferences. In the kampungs, members of various households would traditionally gather and offer whatever they could afford to the host, including cutleries, raw material, fruits, or even labour. Every favour would later be returned in kind when needed.

I remember attending one such kenduri in a small kampung in Negri Sembilan. Tents were laid out on the front lawn of a small wooden house, and under them were numerous pots of lauk, tables and chairs. I asked someone from the host family who had cooked the dishes and he simply replied, “Oh, the chicken came from that house, the goat was from the other house, the plates from there (pointing across the road), and this dish is from this tree (pointing at a coconut tree they had just cut).” He added, “We don’t need to spend anything. Every one helps out.”

Such kenduris were treated as a public event, with an open invitation. Things gradually changed as villages turned to towns and cities. As communal spaces shrank, families occupied elevated spaces, and leisure time made way for work, the kenduri was outsourced to caterers, restaurants and even hotels.

In the course of my work as a documentarian I have conducted hundreds of interviews with old people, and one of my favourite questions to ask is, “What did we Malayans eat 50 years ago?” The answer I usually get is surprisingly simple, “It’s the same as today. Nothing has changed.” The nasi lemak, rendang, char kuey teow, wan tan mee, roti canai we stuff ourselves with today is very much the same as it was before. The finer points of each dish might have changed with the times, but the basic structure of our diet is the same. What has changed though, is our daily routine. People of 50 years ago lead a much more active life than the sedentary lifestyles we have today. They toiled in the fields, walked for many miles to catch the bus, cycled, etc. versus sitting and staring at the computer or smartphone all day long.

Photographs of every day activities help us remember and understand a way of life that is fast disappearing in the face of urbanisation. When viewed in a series, they provide great documentary value, illustrating a constant but rarely noticed evolution in customary practices and culture. The photographs printed in this booklet were taken for posterity, to remember, to cherish.

Technological advancements have made it incredibly easy to make photographs, and yet the intention to document, to cherish and to remember seems to have been left behind with the previous generation. Photography today is all about instant gratification to earn likes, shares and comments, a form of entertainment where we are the creators and consumers at the same time. As we keep looking back to the past to remind us where we are at, I wonder if we will one day look back and wonder what life was like in 2018. There won’t be any photo albums or booklets of prints to look at, only an infinite scrolling timeline on social media. Or maybe we would never bother looking back in the first place.